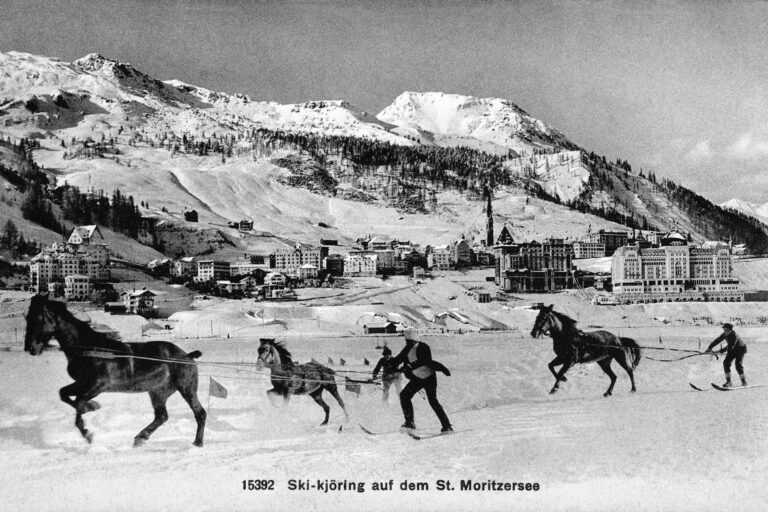

St. Moritz, second race day 2025, Skikjöring: Tension is in the air, the horses are pawing the ground, the skiers are ready. But instead of a rapid start, the unexpected happens: almost all safety systems trigger simultaneously – before the teams even pick up speed. A technical incident that raises questions: How could this happen? And what is being done to prevent such a thing in the future?

What was different on that day?

The analysis shows: On the first race day, everything ran smoothly. On the second, however, it was significantly warmer (+5.1°C) and, above all, drier (only 37% humidity). Exactly this combination favors electrostatic charging – an effect many know from everyday life: the small shock from a doorknob in winter. In the Skikjöring systems, this charge led to a fatal chain reaction. With the exception of a single system, all of them triggered, synchronously across all four release capsules.

The control LEDs of the affected controllers did not flash in the same pattern, but randomly – an indication that no uniform software sequence gave the trigger command. The timing also stands out: All releases happened immediately after the start, when material, movement, and friction can be "electrically charged." Therefore, possible external interferences such as electromagnetic fields (EMF) were discussed – but above all electrostatic discharges (ESD).

Two errors, one effect

The subsequent analysis by experts (A. Bernhard, L. Langhof, and Cypress GmbH) narrowed the events down to two core causes:

The Hardware: The device made of aluminum and chrome steel – particularly the rein release mechanism – can become statically charged at low humidity. Due to the mass and construction of the component, sufficient electrical charge is possible, which finds its way into the controller via the cable.

The Electronics: The printed circuit board (PCB) used until then did not have a dedicated protective circuit against ESD.

In sum, this means: A static voltage "striking" from the outside could act like a false signal on the inside – the electronics interpreted the moment as a command to release. The result was the simultaneous separation of all four capsules in almost all systems.

ESD – the "Doorknob Phenomenon" at the starting gate

Anyone who has ever touched a doorknob in winter and received a small shock knows the principle: In dry air, the body charges up more easily, and the accumulated voltage jumps over as a mini-lightning bolt. Exactly this happened in St. Moritz – only not on a hand, but along a component and cable into the sensitive electronics.

Unlike a powerful electric shock, ESD is usually "high voltage, but low energy": short, steep voltage spikes that can disturb or mislead components without visibly burning them. In the racing situation, factors came together: movement, friction, different materials, cold/heat changes, and – on the day in question – very dry air. This explains why the first race day with high humidity proceeded without incident, while the second mercilessly exposed the weak point.

Why not just make everything mechanical?

A purely mechanical solution sounds tempting but is impractical: Separating four lines simultaneously by hand would require enormous forces and worsen handling. A dead man's switch also carries risks such as accidental releases or missing status indicators. That is why a combination of smart mechanics and robust electronics is used.

The Solutions: Prevention and Protection

To prevent future charges from even getting near the electronics, the release mechanism on the reins and tow line was redesigned so that no conductive contact occurs. The basic idea is simple: What cannot connect electrically cannot pass on a charge. Thus, the "spark" – in both the literal and figurative sense – is defused at the source.

In parallel, a protected controller with several analog and digital protection functions was created. The idea: Even if a static charge gets through, voltages and currents are diverted in a controlled manner. Special components that become "conductive" above a certain voltage offer the current a safe, predefined path – away from the sensitive brain regions of the control unit. Additionally, buffer capacitors smooth out the very fastest voltage jumps. You can imagine this like shock absorbers in a chassis: Small bumps disappear before they throw the system off track.

Limits of feasibility: Why grounding doesn't help here

"Then let's just ground the whole thing," one might think. In this specific case, that falls short: The system is encapsulated; classic grounding – i.e., the safe dissipation of static charges – is constructively not feasible without compromising the protective function of the capsule. An interesting test detail: Even a direct "bombardment" of the capsule, the shielding, and the cable did not lead to a release with the new system. This shows how complex the interplay of geometry, material, and contact points is – and why the chosen mix of prevention (mechanical decoupling) and protection (ESD-hardened electronics) is the most sensible path.

Outlook for 2027

The past winter has shown us that there are setbacks with every invention, but giving up is not an option. This is exactly the path the responsible parties are now taking: with a revised, non-conductive release mechanism and a controller that professionally suppresses voltage spikes. With the current solution, a solid foundation has been laid.

Before the system officially launches again in 2027, extensive test trials will take place on the training track of Skikjöring legend Dury Casty in Zuoz to subject the new technology to final tests under real conditions. Thus, an annoying incident turns into a step forward – so that at the next start only one thing "triggers": the perfect race.